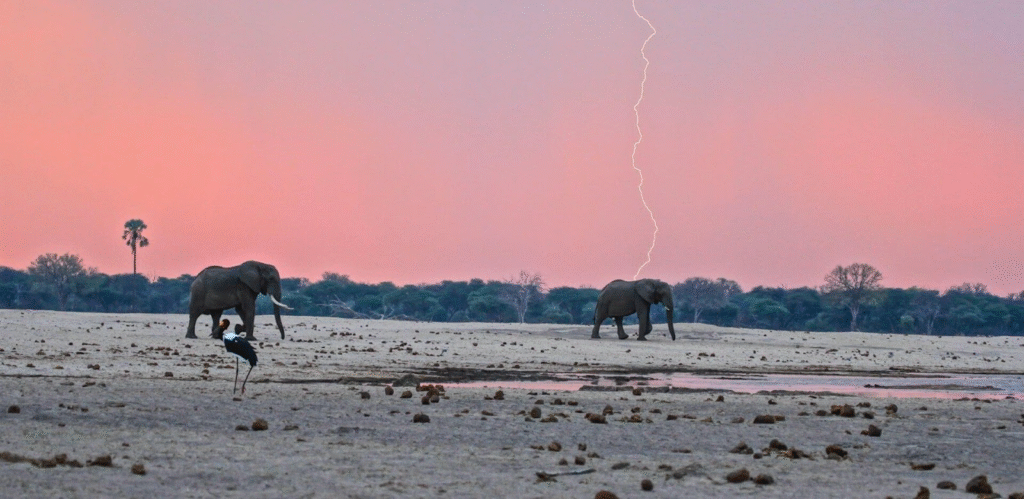

Have you ever stood on the banks of the Zambezi at dawn? The mist rising from the water as hippos grunt from hidden pools and fish eagles call from above – it’s a beauty unlike any other. It’s serene yet filled with veiled danger, calling you back to a forgotten time when nature and humanity were one, where your place in the world was wrapped in a sense of adventure and purpose.

There’s no doubt that this is the image you had in mind when planning your Zimbabwe safari, where the wild rivers, forests, and grasslands call to your soul in a way you can’t quite explain.

Yet beneath this unfathomable beauty lies a difficult question: How should the land be used in a place where wildlife, farming, and human settlement overlap?

The truth is, Zimbabwe’s landscapes have shifted dramatically over the last century. Traditional wildlands have given way to agriculture and expanding towns. What remains is a patchwork of protected parks, private conservancies, villages and communal lands where people and animals need to find equilibrium. This balancing act has shaped the fate of all wildlife in the region, from elephants to lions and countless other species.

Understanding these land use challenges is essential to grasping how conservation can succeed and the role that tourism can play in sustaining it.

From Traditional Wildlands To Agricultural Expansion

Historically, much of Zimbabwe’s territory was unfenced savanna and wetland. Wildlife moved freely across regions, free to follow their natural water and grazing cycles. Back then, human populations were smaller and subsistence farming was concentrated near rivers, leaving plenty of land open for nature to thrive. For centuries, the land supported pocket communities alongside the natural migrations of large mammals.

However, colonial land reforms altered that rhythm. Large tracts of land were designated for commercial farming, and many communities were relocated to make way for civil developments. As a result, much wildlife lost access to key corridors, which meant that protected areas had to be created to compensate for the loss of roaming ground.

National parks such as Hwange, Gonarezhou, Nyanga, and Mana Pools became sanctuaries for these animals, yet these islands of protection were never large enough to carry entire migratory systems on their own.

When Zimbabwe gained its independence in 1980, resettlement programmes were intensified, which ramped up the conversion of farmland, causing the pressure on wildlands to grow.

Zimbabwe’s fertile soils attracted the expansion of several key agricultural products, such as maize, tobacco, citrus and cotton. The grazing lands for cattle also increased as the demand for beef and dairy products ballooned.

The result was that each of these changes narrowed the buffer zones that once linked parks to communal areas, thereby putting both people and animals in closer proximity.

Ecological Consequences for Forests and Grasslands

Today, deforestation remains one of Zimbabwe’s most pressing conservation issues. For example, large swathes of miombo woodland have been cleared for firewood and agriculture. However, as the tree cover has thinned out, the soil has progressively lost much of its fertility, while erosion has accelerated.

This degradation has reduced grazing opportunities for herbivores like antelope, which has in turn affected the predators that depend on them.

Zimbabwe’s grasslands have faced a similar kind of strain. Overgrazing by livestock has degraded the pastureland in many communal areas, which has forced cattle herders to push their herds into zones that are traditionally used by wildlife.

Moreover, in dry years, elephants have been known to raid crops, while predator attacks on livestock increase as their supply of natural prey declines. These conflicts between man and beast have created an environment that is increasingly hostile towards conservation, as rural communities bear the losses directly.

However, the ecological impact reaches beyond just local territories and villages. For example, when woodlands shrink, elephant movements are forced to contract. Species that once depended on intact corridors, such as wild dogs, lose the ability to disperse safely between populations.

What follows is genetic isolation, which undermines the possibility of the species’ long-term survival. Although each patch of cleared land seems small, when it’s multiplied across multiple districts, the effect on the country’s biodiversity is profound.

The Challenge of Wildlife Corridors

Of all the species affected, elephants illustrate the corridor challenge more clearly than any others. Zimbabwe is home to one of the largest elephant populations in Africa, and these animals require vast ranges to feed and breed. These large and magnificent creatures used to traverse regions that now hold farms and settlements, forcing them to contend with fenced boundaries.

Maintaining corridors between Hwange National Park, Mana Pools National Park, Gonarezhou National Park, the Zambezi Valley floodplains, and the Sebungwe region is critical to their survival. However, these routes are under constant threat from agriculture and infrastructure development.

A highway, a cluster of new farms, a mine, or a new irrigation scheme can cause these corridors to be permanently cut off. Once severed, herds become trapped in smaller ranges, which increases pressure on local vegetation to support them and raises the potential for conflict with people who live in the area.

Thankfully, private conservancies have stepped in as a partial solution. In the Lowveld, many landowners have linked former ranches into vast wildlife estates that serve to reconnect fragmented habitats. This model has given large quarry animals, such as elephants and rhinos, renewed space to roam while simultaneously generating revenue from safari tourism.

Nonetheless, the scale of corridor protection that is needed far exceeds what conservancies alone can provide.

Tourism as a Driver of Conservation

The growth of Zimbabwe’s safari industry has become an essential part of addressing these land use challenges. Protected areas and conservancies cannot fund themselves on government budgets alone. Revenue from park fees, lodge stays, safari tours, concession agreements, and even controlled hunting serves to sustain anti-poaching patrols, habitat management, scientific monitoring, and a range of other conservation activities.

In Hwange, for example, lodge-funded boreholes keep waterholes filled during the long dry season, which helps reduce elephant mortality. In Gonarezhou, conservation programmes funded through safari partnerships have managed to reintroduce endangered species such as the black rhino, helping to re-establish populations that have been threatened by poaching.

Beyond wildlife conservation, tourism also provides a practical alternative to land conversion. Many jobs in areas such as tour guiding, hospitality, transport and conservation research have given rural communities a financial reason to value intact wildlands. When a household earns income from lodge employment, the incentive to clear land for crops or engage in poaching decreases. This economic link is a powerful force for strengthening the social contract between people and conservation.

The Role of Responsible Safari Operators

As a traveller, you can play a role in influencing these dynamics through the type of operator you choose. Ethical safari companies will direct their clients toward lodges and parks where revenue directly supports conservation and community projects.

Tailormade Africa, for example, builds itineraries with partners who invest in corridor protection and habitat restoration for the betterment of the natural world.

When booking a Zimbabwe safari, you should look for operators who can explain exactly how your fees are going to be allocated. You should also ask about community partnerships, such as profit-sharing agreements with villages or scholarships funded through tourism revenue.

Before signing up for a safari, assess whether the lodge engages in sustainability practices in areas such as renewable energy, responsible waste management and water efficiency, as these are clear indicators of their level of commitment.

These measures will ensure that your journey does more than just create personal memories for you, but will serve to preserve the environment so that others can enjoy it as well, long after you.

When the land is valued for the wildlife it supports, elephants can keep their corridors, lions can keep their territories, wetlands can continue to provide life-giving sustenance, and communities can keep their livelihoods.

Your decision to travel consciously adds weight to this outcome. Are you planning on going on a Zimbabwe safari? Do you want your journey to directly support conservation and communities? Chat with Tailormade Africa on WhatsApp or give them a call now to design an itinerary that aligns with your values and leaves a positive legacy.